Bleeding mares...

Rupture of and subsequent hemorrhage from the uterine artery

is the most common cause of death in mares after foaling1. In a review of central Kentucky mares,

reproductive complications accounted for the majority (57 of 98 cases) of

deaths in mares around the time of foaling2. Of those that died, rupture of a uterine

artery was determined to be the cause of death in 40 cases (70%). The incidence of peripartum hemorrhage in the

mare has not been determined by retrospective studies of large numbers of

mares, instead reports of clinical cases are found in the literature. Peripartum hemorrhage has been reported to

occur at any age, however older mares are considered to be at greater risk3. Age-related degeneration of arterial vessels

associated with the reproductive tract is suspected to be the reason for the

increased incidence in older mares, coupled with the increased mechanical

stresses imposed by the gravid uterus.

Uterine contractions and obstetrical manipulations further increase

stress on the vessel wall.

Affected mares classically display abdominal pain,

trembling, sweating of the flanks, elevated heart rates, pale mucous membranes,

and varying levels of restlessness. When

severe, mares are agitated to the point of distress, progressing to panic and severe

pain with terminal hemorrhage.

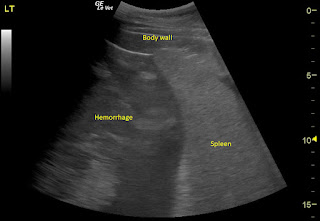

Peripartum hemorrhage can occur in any one the following forms. These are hemorrhage into the peritoneal cavity (image), hemorrhage retained either within the broad ligament of the uterus or within the uterine wall (mural hemorrhage) or hemorrhage into the uterine lumen. Combinations of these may occur necessitating thorough evaluation of mares affected by seemingly less serious forms of hemorrhage to avoid non detection of life-threatening episodes. Hemorrhage into the peritoneal cavity leads to profound hypovolemia, pain and can result in peracute death if sufficiently rapid. If confined to the broad ligament or uterine wall, pain can still be significant but prognosis for life is better. These hematomas may be incidental findings during routine reproductive examinations or may become acutely apparent after foaling following the onset of abdominal hemorrhage. Hemorrhage within the uterine lumen is usually of less significance due to the relatively small amount of blood lost from the circulating pool in most cases.

Although controversy exists as to the utility of various therapeutic agents, ensuring the mare is as calm as possible and not exposed to undue stress is widely agreed upon. Care should be taken during restraint to not excessively stress the mare by using a combination of physical and chemical restraint. Broad spectrum antibacterial therapy is indicated to prevent the establishment of bacterial overgrowth in any hematomas or stagnant pools of blood post hemorrhage. Anti-inflammatory therapy should be maintained following the initial insult to minimize pain and distress, which may lead to increased blood pressure and restarting of hemorrhage. Fluid therapy should be approached with caution and closely monitored. Rapid plasma volume expansion can lead to hemodilution, loss of the hemostatic plug and restarting of hemorrhage. This must be weighed against the necessity of restoration of an adequate circulating volume in the hypovolemic mare as the mare will succumb to hypovolemia not anemia in the acute phase of blood loss4.

Not easy to manage. Definitely

a time to call your veterinarian sooner rather than later.

1. Dolente,

B.A. Critical peripartum disease in the mare. Vet Clin North Am.Equine Pract.

2004;20:151-165.

2. Dwyer,R

and Harrison,L. Post partum deaths of mares. University of Kentucky Equine disease quarterly. 1993;2:5.

3. Arnold,

C.E., Payne, M., Thompson, J.A. et al. Periparturient hemorrhage in mares: 73

cases (1998-2005). J Am.Vet

Med.Assoc. 2008;232:1345-1351.

4. Nolan,

J. Fluid resuscitation for the trauma patient. Resuscitation. 2001;48:57-69.

Comments

Post a Comment